Four months ago, I posted an item on this blog entitled “Pandemics and the Grandfather I Never Knewâ€. That grandfather was Alfred F. Oberjuerge, who died in 1940, 22 years after the Spanish flu nearly killed him in his 20s.

Even before I had completed the Alfred entry, I knew I needed to circle back and write about the other grandfather I never knew.

Edward Lewis Smoot.

My grandfathers must have had many happy moments — weddings, births, holidays.

But each of their lives were marred by physical traumas that eventually left their families in crisis and, as the decades rolled by, turned each of them into hazy figures not well-known by their descendants. Certainly not well-known by this descendant.

Alfred’s burden was dealing with the after-effects of the Spanish flu, which he contracted in 1918, at age 28, while in the navy during World War I. The illness weakened him, and almost certainly contributed to his death at age 50.

For Edward, the disaster was a mine explosion in California’s high desert, circa 1940. It left him with significant brain damage. But he was a tough cowboy and he survived 35 days in a coma.

However, from the moment a compressor in a tungsten mine exploded, he could neither write nor speak nor support his young wife, Natalie, 26, and a daughter who was 6 and a son who was 2.

The medical people diagnosed Edward with “global aphasia” — the most severe form of the condition: “The total loss of the ability to articulate ideas or comprehend spoken or written language, resulting from damage to the brain from injury or disease.”

Edward rejoined his family in Long Beach, California, probably in 1941, and Natalie worked with him, trying to open a line of communication. But he soon became deeply frustrated, and in a matter of weeks or days overwhelmed his family’s ability to care for him. One family member described him as “abusive”. His son said: “He was mentally unstable and destructive as well as suicidal.”

Soon, he was committed to the Veterans Administration hospital in Los Angeles. He lived inside the system until his death in 1972, largely unaware of anything around him for the final three decades of his life, practically forgotten by his own family.

Fleeing from tuberculosis

Edward Lewis Smoot was the second of four sons of Edward Louis Smoot and Alice Magruder, and tuberculosis (TB) explains why a family of nine left the Maryland/Virginia area, where Smoots had lived for 300 years.Â

The patriarch of the clan, Edward Louis, suffered from TB, a lung disease and prominent global killer in the 18th and 19th centuries. One of his daughters, Emma, succumbed to the disease while the family was living in Virginia. Other close relatives struggled to keep TB at bay.

In modern times, the disease has been largely contained, thanks to antibiotics — though 1.5 million global deaths were attributed to tuberculosis in 2018.

In the early 1900s doctors were still searching for a cure.

Some medical people believed that a warm, dry climate could ease the symptoms of TB sufferers, and it was no accident that Edward Louis, not long after the turn of the 20th century, moved his family from Virginia to Imperial, California, near the recently formed Salton Sea and northern Mexico — an area plenty warm and plenty dry. A desert, to be exact.

Edward Louis apparently was a man of some means. He had been in business in Washington D.C., selling coal and wood, before heading west. His father-in-law, Samuel Magruder, a scion of a prominent Virginia family, reported property valued at $20,000 in the 1870 census — which was a lot of equity for a man to have so soon after fighting on the losing side of the Civil War, which ended in 1865.

In Imperial for the 1910 census, Edward Louis Smoot described himself at age 53, as a “contractor†and “employerâ€. It seems likely that his three younger sons — Edward Lewis, 15; Phillip Cornelius, 14; and John Magruder, 10 — provided muscle for the family business, once they finished eighth grade, a fairly common educational milestone in that era.Â

Edward Lewis (not to be confused with Edward Louis, his father) apparently was good with a tractor, but also spent time ranching, farming and tending sheep. He perhaps did not miss many opportunities to engage in social activities, there in sun-baked Imperial County.

In the army

Conveniently, the federal government had a job for him. The U.S. in April 1917 entered World War I on the side of the Allies — Britain, France and Russia — which were ranged against a coalition led by Germany. It was unclear who would win the bloody struggle that had begun in 1914, but the arrival of the American Doughboys seemed likely to make a difference.

President Woodrow Wilson envisioned a multi-million-man U.S. military, far larger than the 100,000-man U.S. force in service as recently as 1914.

American citizens did not immediately succumb to Great War enthusiasm. Six weeks after the declaration of war only 73,000 men had volunteered to go “over there†and fight in the trenches of northern France.

In May 1917 Congress stepped in, creating the Selective Service Act, empowering the government to compel young men into the military. The Smoot boys looked like obvious candidates. Ed, Phil and Johnny were “rough-and-tumble cowboys†according to Edward’s son.Â

Edward Lewis apparently was less than enthusiastic about joining the U.S. military, as were many of his compatriots. When he reported to the draft board in Holtville, near Imperial, on June 5, 1917, he cited his father, 60, mother and two sisters as “dependent relations†who needed him to stay home and provide for the family. Exemptions were often requested, and in many cases fairly reflected the trouble a family would have if a strapping young man were removed from the picture for a year or two. In Edward’s case, the draft board was not moved and he was inducted into the army on September 5, 1918, at El Centro, the seat of Imperial County. By then, the army had gone to the trouble of recording his height (5-foot-7) and weight (155 pounds). His eyes were gray and his hair brown.

Cavalry men? Not so fast

Smoot family lore has it that Edward joined the U.S. cavalry, as did his younger brothers. The 1920 census makes clear Phil and John entered the armed forces, but John joined the navy and Phil spent more than a year in the army. Three brothers all headed for the U.S. cavalry … it didn’t happen.

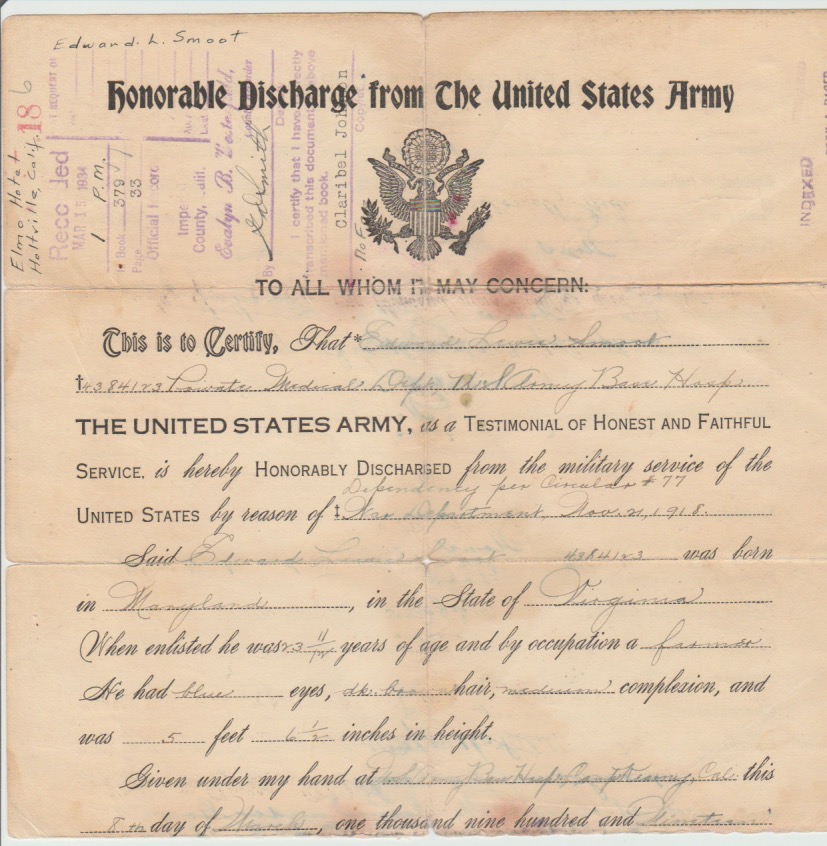

To an extent we can trace Edward, thanks to the Honorable Discharge document (above) he seems to have carried in his wallet from 1919 into the 1940s.

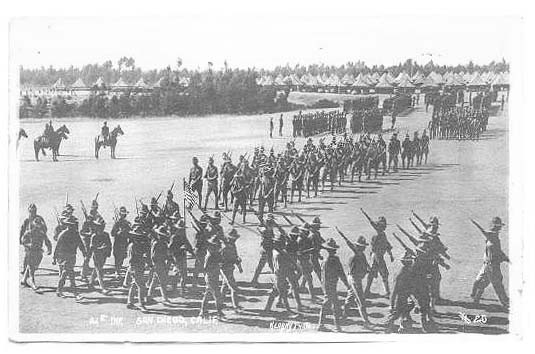

The faded-but-neatly-folded sheet of paper, crumbling a century later, describes him as a private in the medical department at the sprawling army base at Camp Kearny, 11 miles north of downtown San Diego.

He was a member of Company 9, according to his discharge document, and worked at the base hospital from September 27, 1918 until his discharge, on March 8, 1919. (Camp Kearny is now known as the Marine Corps Air Station Miramar.) The war had ended on November 11, 1918, and Camp Kearny thereafter was designated a “demobilization†center.

Like other U.S. soldiers sent home from Camp Kearny, Edward was given $60 and a train ticket. It should not have taken long to return to Imperial, where he then disappears from our view for a decade.

He was not listed in the 1920 census, so he was no longer living with his parents. (They had moved to the more-temperate Redlands, Calif., from Imperial.) Edward Lewis was an army veteran, and that counted for something. But what?

He turned 35 in 1929, the year of the stock market crash and the beginning of the Great Depression. Could he ride out economic chaos by chasing after cattle and sheep or driving a tractor? Perhaps the cowboy ethos would steer him to open spaces and a life with limited responsibilities. He may have mulled that choice as the 1930s dawned.

Marriage and fatherhood

Ah. Here he is. Setting out, a bit late, on the most conventional of life’s paths: That which leads to marriage, ambition and fatherhood. He would need a partner for that.

In 1931 or 1932, George Drinkard, head of household for a farm family, arrived in Holtville from Georgia, where his family had suffered several economic reverses among falling prices for corn and cotton. When their house burned down, they decided it was time to go west.

George and his wife, Meada, had three children. The eldest was Pete, who had been sent out a year or two earlier to have a look at the booming Imperial Valley, which was growing tons of vegetables in bright sun and Colorado River water. He soon became involved in the ice business, crucial to the desert vegetable economy before refrigerated rail cars were common.

Pete was doing well and the family decided it was time to pull up stakes in Georgia and join the rush to California. Pete returned to Georgia to pick up his parents and sisters in his 1928 Ford and, by 1932, they were living in Holtville, where George and Meada ran the Alamo Hotel, as well as a hamburger stand on the main street.

Not all of them were happy about living in Holtville, population 1,700 and the self-declared Carrot Capital of the World. Particularly the middle child, Natalie, who turned 18 in 1932 and was more interested in the California Dream of Los Angeles or Hollywood rather than the dust and tumbleweeds of the Imperial Valley.

However, the move had some social upsides. We hear from Natalie through a five-page unsigned family document that focused on her early life. It seems to have been written after her death, in 1990, and it reveals Natalie’s assessment of life in the California desert, which she found to be “looser†than it was back in Georgia, foremost being the social freedoms she found, away from her pious, “no-fun†parents, as she described them.

It was noted that Natalie encountered beer and playing cards, for the first time, in California. She also was likely to attend Saturday-night parties on the area’s sand dunes. She attended the local junior college. She began to spend more time with her friends than her family.

One of the new friends was Edward Lewis Smoot, a trim, leathery cowboy who cleaned up well and often did not look his age — 38, by late 1932.

On March 22, 1933, Edward and Natalie were married in a civil ceremony in Yuma, Arizona, about 50 miles from Holtville. No witnesses are mentioned, which perhaps is just as well because the bride and groom each fudged their age. Edward was 38 but declared, “upon his oath” in the Arizona Superior Court, that he was 34. Natalie was 18, but she wrote down 23. Thus, what was a 20-year age gap was whittled down to 11 years.

Whatever their birth dates, the marriage seemed to make a turning point in Edward’s life.

Almost overnight he morphed from a foot-loose outdoorsman, a roustabout who bounced around the desert and often bunked in Calipatria, near Holtville, with his brother John and the latter’s wife. Within a year, Edward had a wife and child of his own (Sally Ann, born on a ranch outside Holtville on January 15, 1934) and newfound ambition to make a mark in the world.

The big move

No later than 1936, Edward gave up herding in favor of an industry renown for booms and busts: Mining. And he made a beeline to the California capital of mining in that era, Randsburg, 260 miles north of Imperial in the high desert.Â

His destination, north of Barstow, southwest from Death Valley, had to do with mineralogy and the Randsburg area’s surfeit of precious metals.

Randsburg had been the site of mining for 50 years, It was named after the South African mining town and it was a fitting comparison for half a century. From the 1890s through 1940, gold worth $40 million came out of California’s Randsburg.

Edward, however, was interested in tungsten, a less glamorous but valuable mineral which was found a few miles from Randsburg in 1903. Tungsten has the highest melting point (3,422 degrees celsius) and boiling point (5,930) of any metal. It has numerous applications, including in industrial catalysts, incandescent bulbs, super alloys, radiation shielding and penetrating projectiles. It was a moneymaker.

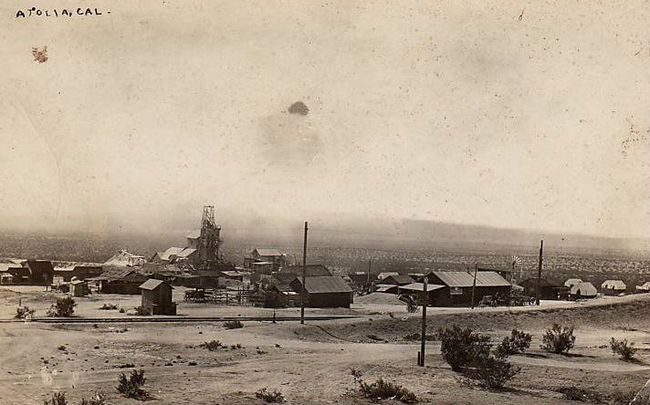

Eventually, so much tungsten ore was brought out of Randsburg that a new city formed around the tungsten sites. It was called Atolia, a contraction of the family names (Atkins and Golia) of the men who owned the Atolia Mining Company. Its heyday was 1916-18, during World War I, when “the mines at Atolia produced more tungsten than any other mine in the world,†according to Randsburg historian Larry Vredenburgh.

Atolia became a classic boom town. In 1916, according to Vredenburgh, it “boasted four restaurants, three general stores, a drug store, two stationery stores, two shoemakers, one hotel, three rooming houses and several lodging tents, four pool rooms, four barber shops, an ice cream parlor, picture show, garage, three butcher shops, a newspaper and new school house for 60 pupils.â€

The best of times

Presumably, Edward Lewis knew about Atolia’s history, and he wanted in, three decades after the area’s heyday. Did he know anything about mining? If he did not, he was a quick learner.

On August 30, 1937, “Ed Smootâ€, as he was known around Randsburg, was mentioned among four men hiring 60 miners to work the Atolia tungsten site, which proved to be productive.

In July of 1938, Ed Smoot was cited in a Randsburg Times story about men returning to work the Atolia mines. Smoot was “manager of the L.C. Main lease and was now working two shifts†— the kind of thing an ambitious man might do.

Ed Smoot had broken into a management role, and his name appeared regularly in the Randsburg Times.

The edition of March 13, 1939, noted a “family reunion†at the house Edward owned in Atolia. He must have been proud, The gathering included his mother, Alice, two sisters, a brother-in-law and a niece — as well as his wife, Natalie, daughter, Sally Ann, and son, Edward Phillip, known as “Sonny†— perhaps because it was hard to keep straight all the Edwards and Phillips in the family.

Ten months later, as 1940 dawned, Edward and Natalie were in the big city at the invitation of L.C. “Dad” Main, a leading figure in the Randsburg mining community. The Times said they “spent the weekend in San Marino with L.C. Main of that city. While there, they saw the Rose Parade and the [football] game between USC and Tennessee.â€

Clearly, Edward is being rewarded by a happy employer/partner, and Natalie, a college football fan, about then might have been thinking, “I did the right thing, marrying Edward.”

In the January 18, 1940, edition of the Times the sixth birthday of Sally Ann was notable for “a party her mother gave for herâ€. Most of Sally’s classmates were there, as well as her teacher, Sue Edwards. “Refreshments served were jello, cake and hot chocolate. They played many games and had a lovely time. She received many lovely presents.â€

In February, a cryptic note: “Pasadena guest; L.C. Main of Pasadena spent the week with Ed Smoot.â€

In the February 29, 1940, Times we read: “Mr. and Mrs. Ed Smoot and Mr. and Mrs. Bradley Dennis made a trip to Los Angeles where they had dinner and saw the show “Gone With the Windâ€. Socializing, like people of means do.

In early 1940, with World War II on the horizon, a U.S. Geological Survey team conducted “Strategic Mineral Investigations†in the Randsburg area and decided a lot of tungsten was still there to be mined.

“The tungsten-bearing fissure veins at Atolia contain the largest bodies of high-grade scheelite discovered in the United States, and possibly in the world.†(Scheelite is often found near tungsten).

Among acknowledgements in their report, the government men noted they were “specifically indebted to Ed Smoot for pertinent information and cordial cooperation.â€

Things had never been better. Edward was a player in the local mining industry. He was given perks from his partner/boss.

In the 1940 census Edward reported working all 52 weeks in 1939 and earning $3,400 in that year, worth approximately $63,000 in 2020 dollars. He owned the family home in Atolia.

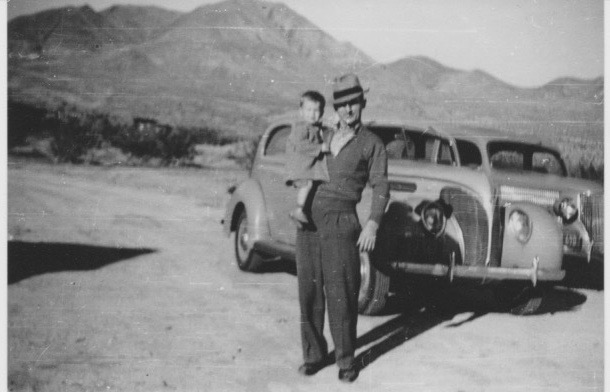

He posed for proud-papa photos of himself with the children, Sally and Sonny. Life was good.

The explosion

It seemed as if fate abandoned Edward even as he continued to climb the ladder of success, because things went bad fairly quickly.

The first hint that something was amiss comes in the Randsburg Times of October 3, 1940. “Smoots visit Atolia friends.†To wit: “Mr. and Mrs. Ed Smoot, former residents of Atolia, visited in this community Thursday of last week.â€

So, the Smoots no longer live in Atolia, in the place Edward had owned? Why should that be?

The second hint is … silence. From October 3, 1940, to the following February not a single reference to Edward or his family appeared in the Randsburg Times.

Nothing on birthday parties at school. No drives to Los Angeles for dinner and a show. Nothing about Christmas, nothing about the New Year, which Edward and Natalie had ushered in the previous January 1 in Pasadena. This is worrisome.

Then this, under the label “Family visitsâ€.

“Mrs. Ed Smoot accompanied by their children was here on Monday to visit Mr. Smoot.â€

It was the last reference the newspaper made to Edward or his family.

We know the basics of what happened: An explosion sometime between October 3, 1940, and February 13 of 1941. The exact date is lost to history.

Edward was in a mine when a compressor exploded, spraying shrapnel. His daughter, Sally, about 7 at the time, said one of her earliest memories is hearing the “accident siren” wailing from the mine. No one but Edward was hurt, but his injury was dire: His brain was badly damaged.

It is unclear if the whole of the Atolia-Randsburg area had a full-time doctor, never mind a brain specialist. Edward survived, but he was in a coma for five weeks. What sort of care did he receive? A family document indicates that, eventually, a brain surgeon from Los Angeles traveled to the high desert to operate on Edward, to do what could be done.

The aftermath

Job 1 was housing for Natalie and the kids, with Edward in the hospital. Brother Phil and sister-in-law Florence, stepped in. Phil worked as a mechanic for a local diary and owned a home in Long Beach, Calif.

That allowed Natalie time to catch her breath.

Natalie in 1942 took a job with Pacific Telephone Company; she would hold that job for 30 years. In 1943, with family help, Natalie bought a home in Long Beach. Initially, they took in boarders. After her father died that same year, Natalie’s mother moved in. Grandma Drinkard did the cooking and housekeeping.

“Grandma Drinkard, Sally and I shared a tiny bedroom with a Murphy bed off the kitchen,” Edward’s son said. “We raised rabbits, chickens, and vegetables.”

They lived in the Long Beach house through the rest of the 1940s.

By then, Edward Lewis was becoming a forgotten man.

After the disastrous attempt to have Edward live with his wife and children, his brother Phil, and Natalie, asked the authorities to have Edward sent for long-term care with the VA. The request was carried out. Edward probably had no idea what was going on, as he went off to spend the rest of his days in L.A. or San Diego VA hospitals.

He apparently was known to love Coca-Cola and chocolate

Odd reactions

When the conversation turned to his final days at the mine, one topic often came up — the seemingly callous treatment of Edward’s wife and children by L.C. Main.

Edward worked with Main for several years but family history suggests Main, after the explosion, wanted the Smoots out of the Randsburg area as soon as possible, and he made that sentiment quite clear to Natalie.

Her son, Edward Philip, said: “I have no idea why or how we were booted out of our house, but it was fast and nasty. It may be my imagination, but we left with only personal effects in a car and little else.â€

Curiously, the Randsburg Times, which was enthusiastic about children’s birthday parties, printed nothing about how one of the more prominent miners in the area had almost been killed and was hovering between life and death.

Nearby newspapers, such as the Bakersfield Californian, typically reported on deaths in the mining industry, which were not uncommon. Perhaps 35 days in a coma was not newsy enough. Perhaps the story of the explosion never got out of the Randsburg area. After all, no one died. It was as though the explosion never happened.

Perhaps it would reflect badly on a local industry that was more than a little dangerous, especially when digging began or the TNT came out.

Hope against hope

Had Edward been injured in modern times, the medical outcome might have been different.

Therapy and medication can sometimes help, in 2020, or work-arounds can be attempted — communicating without speech, for example. But 80 years ago, no, it was beyond unlikely that an global aphasia victim would regain the ability to speak. Natalie yielded to reality.

Forgotten man

Edward received few visitors. His son, Edward Phillip, who was born in 1937 in a clinic above the bar in Randsburg, had been called “Sonny†by his father, and he saw the man as much as anyone in the family, over the next three decades.

He recalled: “When I visited the first time my dad became very agitated as we approached, so we backed off. We were told he understood quite a bit but did not converse. The next few visits I just observed him and did not approach, as suggested by the medical staff.â€

He was told his Aunt Edna, Edward’s sister and the family historian, wrote to his father regularly, keeping him up to date on family affairs. “Supposedly, Edna’s letters were read to him, but he was not very responsive,†Edward Phillip said.

“I never saw him speak.â€

A common side-effect of aphasia is an inability to recognize time moving forward. Victims are stuck in the world as it was when they were injured. Edward Lewis became agitated at the sight of his son, Edward Phillip, because he did not recognize his growing boy. He remembered only the toddler in Atolia.

The end

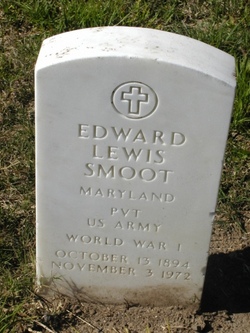

Edward Lewis died in San Diego on November 3, 1972, at the age of 78.

His certificate of death was a litany of dire conditions: “Respiratory failure, severe cortical atrophy, subdural hematoma and residuals, generalized arteriosclerosis, chronic urinary infection, colitis.”

Edward’s son was the only person to see his father’s body at a Tustin funeral home. Three relatives turned out for the graveside service at the national cemetery near UCLA — Natalie, her son and his wife. Edward’s three brothers were still alive, but they did not go to see their brother’s interment.

I could have gone. I was 19, the oldest of his eight grandchildren. But I had no idea Edward Lewis had died. He was not talked about.

Natalie moved on with her life. She worked for Pacific Telephone for 30 years and she had many happy years with Hassel Norman, a Texan who also had a bit of the cowboy flare, and was often treated as a grandfather.

I would guess that neither Alfred F. Oberjuerge nor Edward Lewis Smoot would describe himself as unlucky or jinxed. They recognized that their world was a dangerous place. Pandemics, explosive compressors, primitive pharmacology … things happened, and back then people were not as easily surprised.

Alfred knew his health was compromised, but he was able to lead a relatively normal life after his recovery from the Spanish flu and into 1940. He could say goodbye to loved ones, perhaps get his affairs in order before a final encounter with illness.

Edward’s situation seems harsher. For most of three decades he seemed to be a man who was not making an impression on the world. Then came marriage, and it all changed — two children in four years, success and respect in a technical field, a quick climb into management and recognition from federal officials as someone who knew his stuff.

And then what must have felt like the lights going out. Five weeks in a coma. Unable to speak or read. Grandkids he did not know existed. Vaguely aware something was wrong, powerless to do anything about it. More than three decades behind closed doors, known on the ward as the guy who loves Cokes and chocolate.

Or was it all that bad? His son wonders.

“He lived a quiet, peaceful, reasonably healthy life with no real interface with the world around him for 33 years,†Edward Phillip wrote.

“Today, the sort of injury he experienced could likely have been successfully treated with current medical technology.

“My dad was very bright, tough and a hard worker and, I understand, a good father. I believe he treated our mom with love and respect.â€

Edward was buried in the Los Angeles National Cemetery, under a headstone that provides his name and this note: “PVT US ARMY WORLD WAR Iâ€. Three people were in attendance for the gravesite service: Natalie, Edward’s son and his daughter in law. His three brothers were alive but did not attend. Neither did I.

I was 19 when he died; I could have gone to the cemetery, but I did not know he had passed away.

I am sad I do not know more about him, but between his peregrinations as a young man and the injury that silenced him in mid-life … he is a difficult man to track down, or figure out.

As is the case with my patrilineal grandfather, Alfred, I would love to talk to Edward, tell him his story is not forgotten and at least let him know that 20 years into the 21st century he has 38 direct descendants, with more on the way.Â

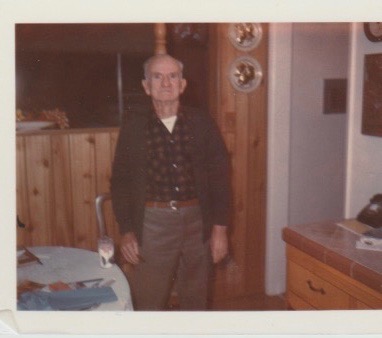

The final photo we have of him comes from his son’s visit to a private living facility near the San Diego VA hospital. (Photo at beginning of blog) The staff helped stage the moment: Just behind Edward is something that looks like a seat on wheels.

His son said: “They had spiffed him up for the picture. I’m not sure he totally grasped what was occurring. The staff was very kind and gentle with him, and he was very docile.

“He had no idea who I was.”

1 response so far ↓

1 Cindy Robinson // Aug 11, 2020 at 6:53 AM

Wow, what a great history — and what a tragedy. Sounds like this should be made into a movie. Very well written. You have inspired me to look more into my family own history before it’s totally forgotten. I enjoyed reading it. Labor of love.

Leave a Comment