The wind blows sometimes, here in the south of France.

In the summer, that can pose problems with slamming doors, because we like to keep the windows open throughout the season, when it can be a bit warm. And gusty.

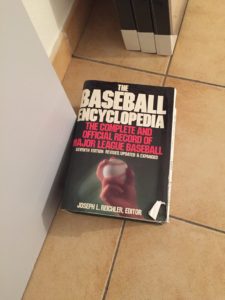

Thus, we prop open the doors with compact and heavy things lying about.

An old iron. Water bottles. A potted plant.

Yes, The Baseball Encyclopedia. The massive reference book (all seven pounds of it) of America’s pastime. The book on my desk, of which I said, years ago: “If a fire sweeps this building and I can save only two things, it will be The Baseball Encyclopedia … and something else.”

The tome that led Stan Musial to say: “Everything you’ve always wanted to know about baseball but couldn’t find in one place before. … The amount of information is staggering.”

The book that led Reggie Jackson to say: “If you can’t find it here you won’t be able to find it anywhere. This is the finest baseball record book in existence.”

A book not long ago considered essential to the library of every newspaper sports section in America. A book that covered 2,875 pages in the seventh edition, printed in 1988, and cost $45 — which was real money, 30 years ago.

Now sitting on a bedroom floor at our home, collecting dust.

And as I walked past it the other day, it struck me that the near total eclipse of The Baseball Encyclopedia by online resources like baseballreference.com … was not unlike the trampling of print journalism by the internet. And almost as painful.

The Baseball Encyclopedia allowed news organizations to have a thorough compilation of all the basic statistics ever compiled in a Major League game.

In the seventh edition, that meant every player who had played in a big-league game from 1876 through the 1987 season. Even Archibald Wright “Moonlight” Graham, who appeared in one game with the New York Giants in 1905 but did not get a chance to hit. (See: Burt Lancaster in Field of Dreams.)

This made the encyclopedia a particularly important resource. For editors and reporters and, especially, baseball writers. One volume — a big one, granted — with everything in it. (And for sports clerks, who were asked to settle bar bets by looking up a stat in TBE.)

By today’s standards, the TBE was not complete.

The first Baseball Encyclopedia was printed in 1969, and through the 1987 season it never displayed what for a generation has been considered a key statistic — on-base percentage — nor did it have OPS (on-base plus slugging). And it certainly did not have what has come to called advanced metrics such as WAR (wins above replacement).

But it was so far superior to anything baseball had before. For position players, it contained every game, at-bat, double, triple, home run, run, RBI, walk, strikeout, stolen base (but not caught stealing), batting average, slugging average, pinch hit and games-by-position.

It was mind-boggling, The Baseball Encyclopedia. A historian with imagination could almost recreate the history of the game simply by looking at the mound of numbers, and various footnotes.

During its heyday, which lasted about 30 years, The Baseball Encyclopedia was essential. It was the Bible of baseball.

And now it sits as a doorstop in my home.

It was nostalgia, maybe with a bit of ballpark romance, that led me to salvage the book from the old offices of The San Bernardino Sun, to store it for more than six years and to have it shipped over to France last year.

I can’t actually say I have needed to refer to it, since it arrived, a year ago. I have an internet connection. I can call up any player’s history on my laptop screen in a matter of seconds.

But the encyclopedia reminds me of days past, and careers past, on and off the field, and if I want to hold those memories in my hands, well there is always the doorstop on the upper floor.

0 responses so far ↓

There are no comments yet...Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment